[ad_1]

Iran has vowed retaliation for an Israeli attack on its consulate in Damascus last Monday.

The strike was part of a pattern of escalated Israeli attacks in Syria since the eruption of the Gaza war last October. These attacks have often targeted warehouses, trucks, and airports, and Israel’s declared aim for them is degrading Iran’s transnational supply network for the Lebanese group Hezbollah.

Monday’s attack was different, however, in that it struck a diplomatic facility – directly challenging Iran’s sovereignty – and killed senior leaders in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

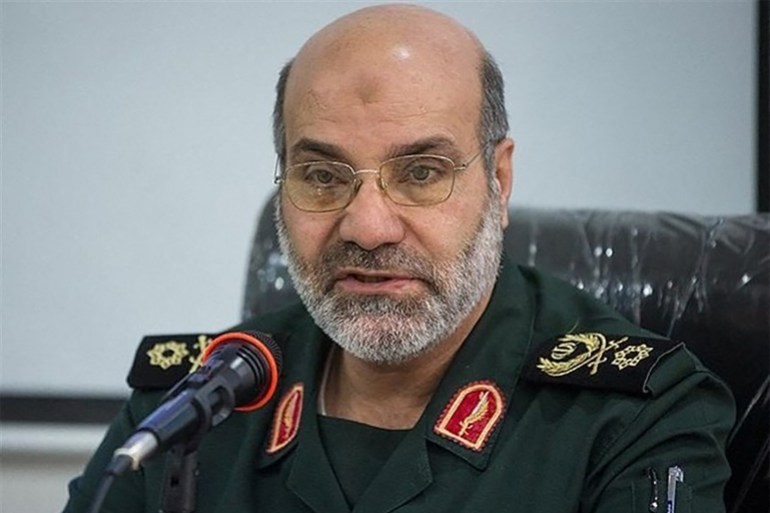

The most high-profile casualty was Brigadier General Mohammad Reza Zahedi, a veteran commander who led the IRGC foreign operations wing, the Quds Force, in Syria and Lebanon.

How will Iran respond? As it turns out, Tehran has a lot of options – but none of them are very good.

Allies and power politics

A major player in Middle East politics, Iran generally projects its power through a network of ideologically aligned allies and non-state groups – a network that styles itself the “Axis of Resistance”.

These groups include the Houthis of Yemen, Hamas of Palestine, Hezbollah of Lebanon, and Shia militia factions like Kataib Hezbollah in Iraq, plus Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria.

The actors fall on a spectrum ranging from hardcore IRGC loyalists and proxies, like the two Hezbollahs, to autonomous but often dependent partners and allies of Tehran, like Hamas, the Houthis, and the al-Assad regime.

Collectively, they benefit from Iranian support while their actions help Iran maintain deniability and keep its conflicts with Israel, the United States, and Gulf Arab states like Saudi Arabia at arm’s length.

In 2020, however, Iran took the unusual step of responding to the US assassination of the Quds Force leader Qassem Soleimani – which was itself unprecedented – by staging a direct attack on US forces, launching a barrage of ballistic missiles at the Ain al-Assad base in Iraq.

US soldiers at the base were injured but none were killed, in large part because they had received warning from the Iraqi government.

It was an impressive demonstration of Iranian missile technology, but underwhelming as a retaliatory action.

Iranian leaders continued to voice vague threats about additional future retaliation and helped Iraqi militias harass US forces – and, over time, the urgency of it all faded away.

A bad moment for escalation

Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is seen as being in a bind. It is widely assumed that he wants to retaliate visibly, not just to avenge the killing of senior officials but also because not doing so would tarnish Iran’s credibility as a regional power.

But now is not a good time. The region has been aflame since the start of the Gaza war, following Hamas’s October 7 attack in Israel, which killed more than 1,100 Israelis, and the Israeli government’s brutal response, which has killed more than 33,100 Palestinians thus far and pushed Gaza into famine conditions.

Since October, vicious tit-for-tat violence has raged along the Israel-Lebanon border, there has been a long string of attacks on US forces in Syria and Iraq, and Red Sea shipping has been disrupted by Houthi missile and drone strikes.

Although methods and targets differ from country to country, these attacks all enjoy Iran’s support and they all aim to pressure Israeli and US leaders to stop the war in Gaza.

Even though Iran may be willing to tolerate the risk of an accidental regional war, it has repeatedly shown that it does not want direct conflict with Israel or the US and will try to keep violence below that threshold.

When Iran-backed groups killed three US soldiers in Jordan earlier this year, Washington retaliated with air attacks on Syria and Iraq.

Tehran seemed to back down: Quds Force commander Esmail Qaani reportedly told pro-Iran factions in Iraq to stop targeting US troops. Since then, they have mostly been sending drones against Israel, with little effect.

But failing to respond – or responding only through low-key proxy actions – does not seem like an option for Tehran, given that it has publicly committed itself to avenging the consulate attack.

Khamenei has said Iran’s “brave men” will punish Israel, one of his advisers has warned that Israeli embassies “are no longer safe”, and two officials recently told the New York Times they will retaliate directly against Israel, to restore deterrence.

Failing to live up to these public threats could make Iran seem weak in the eyes of friends and foes alike, potentially putting it at a disadvantage during regional unrest and signalling to Israel that continued escalation carries no cost.

Iran is likely also concerned that attacks on Iranian high-level officials and state assets could become a normal feature of its tit-for-tat conflict with Israel, at a very bad moment in time.

Keeping conflict with Israel and the US under control was always an important goal of Iranian foreign policy. But it is doubly so now, given that the most anti-Iranian president in contemporary US history, Donald Trump, may be about to reclaim the White House.

From Tehran’s point of view, surrendering control over the escalatory dynamic to Israel just before the start of another Trump presidency would be very, very bad policy.

Many options, all problematic

What to do? Iran has many powerful proxies and allies in the Middle East, but none of them seems well placed to effect a retaliatory action calibrated to Iran’s concerns about longer-term risks.

The Houthis in Yemen have been waging a highly successful campaign against merchant shipping since last year, using Iranian-supplied arms. But although they have also shown themselves capable of launching high-tech Iranian missiles and drones at southern Israel, those attacks are not very effective.

US and European warships have set up a thick layer of air defences along the Red Sea, and Israel’s missile defences have been able to knock down most of whatever gets through that gauntlet.

The Houthis have struggled to hit Israeli territory, and even then it did not affect the war in Gaza or regional dynamics meaningfully. In other words, while Iran could enable and encourage ramped-up Yemeni strikes, it would probably not do much to help it out of its deterrence quandary.

Khamenei’s problem is that his best tools against Israel are also the ones most likely to draw a harsh Israeli response and trigger uncontrollable escalation – which might end badly for Iran.

For example, Iran seems perfectly capable of replaying its 2020 reaction to the death of Soleimani, by firing a volley of ballistic missiles into Israeli territory.

But even if the impact were fairly minor – if the missiles crash into the empty desert or detonate without deaths in an isolated military facility – a post-October 7 Israel is likely to respond ferociously, potentially overshadowing and nullifying the symbolic impact of Iran’s missile strike. It is not likely to seem an appealing outcome to Iran, given that the central plank of its strategy has been to avoid a direct war.

Retaliating at scale via Lebanon is another option. Iran has spent decades boosting Hezbollah’s rocket and missile arsenal, equipping the group with sophisticated ballistic and cruise missiles, and drones. Most of these precision weapons have not been used in the post-October conflict, but they are on hand for any decision to escalate.

Major attacks from Lebanon would, however, mean playing one of Hezbollah’s best cards early, and it would also run the risk of destabilising an already dangerous and fragile situation on the Israel-Lebanon border, which is precisely what Iran and Hezbollah have tried to avoid.

The idea has been to keep border violence at a controlled simmer since October 2023, as a way of drawing Israeli resources away from Gaza while incentivising a conflict-averse US to put a leash on its belligerent Israeli ally.

A major strike from Lebanon to burnish Iran’s deterrence credentials does not seem compatible with that kind of high-stakes balancing.

The ‘diplomatic option’

Iran may try to hit Israeli diplomatic facilities, to project eye-for-eye retaliation after Israel’s attack on the Damascus consulate. As a precautionary measure, Israel has reportedly shuttered 28 embassies worldwide.

Any Iranian strike on an Israeli diplomatic facility would be unlikely to kill a Zahedi-type security chief and thus would not really be comparable to Israel’s attack.

But even a minor attack on an Israeli embassy or consulate could help Iranian leaders argue that they have now evened out the score: you hit our diplomatic facilities, we hit yours.

An attack on a diplomatic facility could be overt, using missiles or drones launched from Iranian territory. It would damage Iran’s relations with the host nation involved, but depending on which nation that is, Tehran may be willing to accept some political drama.

Last January, Iran fired ballistic missiles at what it claimed was a Mossad base in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq – without offering evidence – while also striking unrelated targets in Syria and Pakistan.

It was a strange, sudden way of lashing out, and it is not clear that the strikes had any effect other than demonstrating Iran’s ability to hit distant targets and make itself seem dangerous and unpredictable – which may have been the intended effect.

Repeating that strike now would be a low-risk course of action. Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) authorities are unable to respond in any meaningful fashion and while the central government in Baghdad might react angrily, the fallout would surely be manageable.

Still, it is not clear that blowing up another piece of KRG territory would satisfy those Iranian and Axis hardliners who want to see serious vengeance after Zahedi’s death. In other words, even if convenient, such an attack might not be enough by itself.

Covert action – like unclaimed drone strikes, assassinations, or bombings, perhaps via Hezbollah or some other proxy – is another option. Iran has done it before and still remains capable of doing it.

Then again, the less overt the attack and the longer it takes to execute, the less it will help Iran’s deterrence. While killing an Israeli diplomat might be counted as a success for Iranian leaders, the problem they need to solve is how to make Israel and others think twice about bombing Iranian assets.

Talk loudly while carrying a small stick

In sum, Iran has strong reasons to react forcefully to Israel’s Damascus attack – and even stronger reasons to make sure that its response is not perceived as too forceful.

Moreover, it has many ways of attacking Israel, whether through its own military capabilities or semi-covertly through the Axis of Resistance network of pro-Iran factions.

And yet, the sum of all these parts does not add up to much. None of Iran’s retaliatory options seems well-adapted to the current situation, in which the stakes are already uncomfortably high due to the Gaza conflict.

The available means of retaliation will either not generate enough symbolic and material impact to let Khamenei and his cohorts claim they have settled the score – or they will, but at the cost of uncontrollable and probably unacceptable risks to Iran’s longer-term security.

It is likely then that Iran will have to make do with another underwhelming response or set of responses.

As in 2020, it must then do its best to patch up the all-too-visible holes in its deterrence posture with fiery rhetoric. No amount of angry statements can harm Israel or dissuade it from attacking again, but they can at least provide some temporary comfort to the Axis of Resistance hardliners.

[ad_2]

Source link